iptables-restore < /etc/iptables/rules.v4

iptables-save > /etc/iptables/rules.v4

iptables: Too many links.

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT) target prot opt source destination Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT) chain having the referenced rules target prot opt source destination customChain2 all -- anywhere anywhere referenced rule customChain1 all -- anywhere anywhere referenced rule ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere ACCEPT all -- anywhere anywhere Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT) target prot opt source destination Chain customChain1 (1 references) references are mentioned explicitly target prot opt source destination Chain customChain2 (1 references) references are mentioned explicitly target prot opt source destination

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT) target prot opt source destination Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT) target prot opt source destination Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT) target prot opt source destination Chain customChain1 (0 references) as expected target prot opt source destination Chain customChain2 (0 references) as expected target prot opt source destination

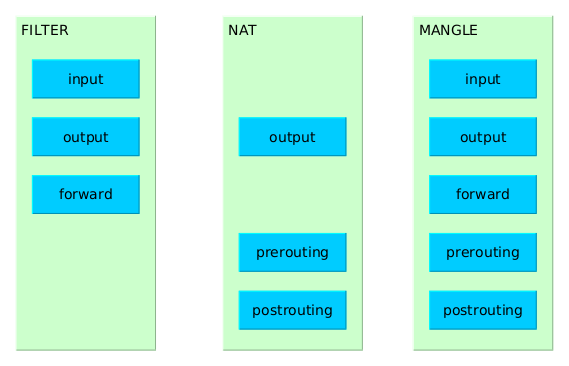

| Table | Usage | Chains | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| filter | default table | INPUT | applies to packets received via a network interface |

| OUTPUT | applies to packets sent out via the same network interface which received the packets | ||

| FORWARD | applies to packets received on one network interface and sent out on another | ||

| NAT | can be used to modify the source and destination addresses recorded in packets | PREROUTING | alters packets received via a network interface when they arrive |

| OUTPUT | alters locally-generated packets before they are routed via a network interface | ||

| POSTROUTING | alters packets before they are sent out via a network interface | ||

| mangle | allows to alter packets in specialized ways | PREROUTING | alters packets received via a network interface before they are routed |

| OUTPUT | alters locally-generated packets before they are routed via a network interface |

service iptables save service iptables restartBut after rebooting, the rules are lost. How to fix this ?

iptables is designed to flush all rules when stopping (which is normal since stopping iptables means stopping filtering). service iptables stop outputs :

iptables: Saving firewall rules to /etc/sysconfig/iptables: [ OK ] iptables: Flushing firewall rules: [ OK ] iptables: Setting chains to policy ACCEPT: filter [ OK ] iptables: Unloading modules: [ OK ]

IPTABLES_SAVE_ON_STOP="yes" IPTABLES_SAVE_ON_RESTART="yes"Fix values if necessary.

iptables 0:off 1:off 2:on 3:on 4:on 5:on 6:off

| Command | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|

| -A chainName | Append a rule at the end of chainName | |

| -D | Delete rule number n from chainName n is given by --line-numbers |

iptables -t tableName -D chainName n |

| -d | specify the destination (IP or hostname) in a rule definition | |

| --dport --destination-port | specify the destination port in a rule definition.

This flag can be specified only when specifying some specific protocols (including tcp and udp), not all protocols have ports (details).

More : man iptables-extensions, search --protocol tcp |

|

| -E | rename a (user custom) chain | iptables -E oldChainName newChainName |

|

-F --flush |

Flush a chain : delete all rules of that chain (all the chains in the table if none is given) | iptables -F chainName |

| -I chainName ruleNb | Insert a rule into chainName at the ruleNb position | -I INPUT ruleNb |

| -i | input interface via which a packet is received (for packets entering the INPUT, FORWARD and PREROUTING chains) If this option is omitted, any interface will match. |

|

| -j | jump to target. "target" is what to do with the packet when the rule matches. Most common targets are:

|

|

|

-L chainName --list chainName |

List rules of chainName (if not specified, defaults to filter = list existing rules) | iptables -t tableName -L chainName |

| --line-numbers | display line (=rule) numbers while listing rules with -L | iptables -t tableName -L chainName --line-numbers |

|

-m extensionModule --match extensionModule |

Use the module extensionModule to match packets : | iptables -t filter -A chainName -m state --state ! INVALID |

| --mac-source | specify the source MAC @ of a packet as a filtering criteria | iptables -t filter -A chainName -m mac --mac-source XX:XX:XX:XX:XX:XX |

|

-N chainName --new-chain chainName |

Create a new user-defined chain called chainName. chainName must not already exist. | iptables -N myChain iptables -A myChain (rule definition) |

| -n --numeric | Print IP addresses and port numbers in numeric format | |

| -o | output interface via which a packet is going to be sent (for packets entering the FORWARD, OUTPUT and POSTROUTING chains) If this option is omitted, any interface will match. |

|

| -P | change Policy of a chain | iptables -P FORWARD ACCEPT |

|

-p protocol --protocol protocol |

specify the protocol in a rule definition. protocol can be one of :

|

|

| --state NEW | match packets which state is NEW | |

| -s | specify the source (IP or hostname) in a rule definition | |

| --set | add the source address of the packet to the list (when used with the recent module) | |

| -t tableName | specify a table to consider | |

| -v | verbose. When used with -L, displays the number of matched packets / bytes for each rule. | |

|

-X userDefinedChain --delete-chain userDefinedChain |

Delete the userDefinedChain chain, which must be empty (i.e. contain no rule) If no argument is given, it will attempt to delete every non-builtin chain in the table. |

|

| --source-port | specify the source port in a rule definition | See --destination-port for examples. |

| ! | negation. Can be used with address, protocol, interface name, ... | |

| + | wildcard for interfaces names (to be used with the -i and -o options). "abc+" will refer to any interface which name starts with "abc" | |

iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -p tcp --dport sourcePort -j REDIRECT --to-ports destinationPort

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

num target prot opt source destination

7 ACCEPT udp -- anywhere anywhere udp dpt:12345 /* Don't panic */ shown as C-style comments : with /* and */

sources : http://www.thegeekstuff.com/2011/06/iptables-rules-examples/ https://www.cyberciti.biz/tips/linux-iptables-4-block-all-incoming-traffic-but-allow-ssh.html https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/iptables-essentials-common-firewall-rules-and-commands https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/108169/what-is-the-difference-between-m-conntrack-ctstate-and-m-state-state#!/bin/bash # flush all rules iptables -F iptables -X # set default filter policy iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT iptables -P FORWARD DROP # allow unlimited traffic on loopback iptables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT iptables -A OUTPUT -o lo -j ACCEPT # allow related+established traffic iptables -A INPUT -m state --state ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT #iptables -A OUTPUT -m state --state ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT # allow some specific + limited incoming traffic interface='enp2s0' port='443' iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport $port -i $interface -m state --state NEW -m recent --set iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport $port -i $interface -m state --state NEW -m recent --update --seconds 60 --hitcount 5 -j DROP

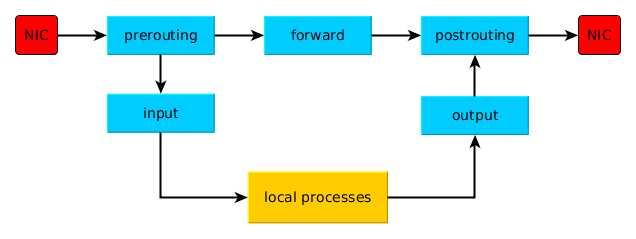

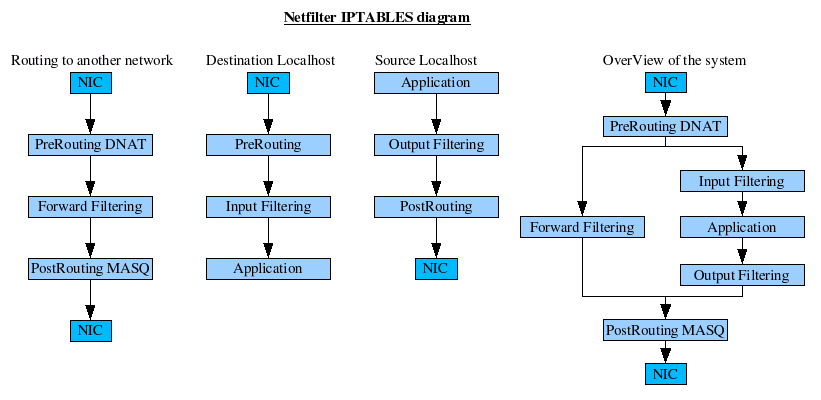

iptables a.k.a. Netfilter examines incoming and outgoing packets at various points (known as inspection points). It does this by matching each packet against a chain of rules. Each rule contains matching criteria and a target which says what to do with a packet that matched the criteria. Packets are matched against each rule in a chain, in order, until a match occurs. Then the target of that rule is used (generally) to accept or to drop the packet. However the target may cause the packet's header fields to be changed, to log the packet, or do another action. If no rule matches some packet then a default policy is used to decide what to do.

iptables is a stateful packet filter, in that it keeps track of connections, statistics, and packet flows. Even UDP packets can be tracked (e.g., a DNS query and the response). All that information may be used in the criteria to match packets, or to produce reports. Note that connections have a timeout value, so iptables may "forget" some long idle connection and begin dropping packets.

Besides packet filtering, iptables collects statistics on byte and packet counts for each rule. This is called IP accounting.

Every network packet received by or sent out of a Linux system is subject to at least one table.

The "I" below is not myself, I'm not the author of this article. I got it from the Internetz a long time ago and can't find the original source (if still online). Should you have any information regarding the author or source, please let me know : I'd be happy to give credits with a "source" hyperlink .

I'm sure many of you have been wondering how to use iptables to set up a basic firewall. I'll try to explain the basics to at least get you started.

First you need to know how the firewall treats packets leaving, entering, or passing through your computer. Basically there is a chain for each of these :

Now the way that iptables works is that you set up certain rules in each of these chains that decide what happens to packets of data that pass through them. For instance, if your computer was to send out a packet to http://www.yahoo.com/ to request an HTML page, it would first pass through the OUTPUT chain. The kernel would look through the rules in the chain and see if any of them match. The first one that matches will decide the outcome of that packet. If none of the rules match, then the policy of the whole chain will be the final decision maker. Then whatever reply Yahoo! sent back would pass through the INPUT chain. It's no more complicated than that.

Now that we have the basics out of the way, we can start working on putting all this to practical use. There are a lot of different letters to memorize when using iptables and you'll probably have to peek at the man page often to remind yourself of a certain one. Now let's start with manipulation of certain IP addresses. Suppose you wanted to block all packets coming from 200.200.200.1. First of all, -s is used to specify a source IP or DNS name. So from that, to refer to traffic coming from this address, we'd use this:

iptables -s 200.200.200.1

But that doesn't tell what to do with the packets. The -j option is used to specify what happens to the packet. The most common three are ACCEPT, DENY and DROP. Now you can probably figure out what ACCEPT does and it's not what we want. DENY sends a message back that this computer isn't accepting connections. DROP just totally ignores the packet. If we're really suspicious about this certain IP address, we'd probably prefer DROP over DENY. So here is the command with the result:

iptables -s 200.200.200.1 -j DROP

But the computer still won't understand this. There's one more thing we need to add and that's which chain it goes on. You use -A for this. It just appends the rule to the end of whichever chain you specify. Since we want to keep the computer from talking to us, we'd put it on INPUT. So here's the entire command:

iptables -A INPUT -s 200.200.200.1 -j DROP

This single command would ignore everything coming from 200.200.200.1 (with exceptions, but we'll get into that later). The order of the options doesn't matter; the -j DROP could go before -s 200.200.200.1. I just like to put the outcome part at the end of the command. Ok, we're now capable of ignoring a certain computer on a network. If you wanted to keep your computer from talking to it, you'd simply change INPUT to OUTPUT and change the -s to -d for destination. Now that's not too hard, is it?

So what if we only wanted to ignore telnet requests from this computer? Well that's not very hard either. You might know that port 23 is for telnet, but you can just use the word telnet if you like. There are at least 3 protocols that can be specified: TCP, UDP, and ICMP. Telnet, like most services, runs on TCP so we're going with it. The -p option specifies the pprotocol. But TCP doesn't tell it everything; telnet is only a specific protocol used on the larger protocol of TCP. After we specify that the protocol is TCP, we can use --destination-port to denote the port that they're trying to contact us on. Make sure you don't get source and destination ports mixed up. Remember, the client can run on any port, it's the server that will be running the service on port 23. Any time you want to block out a certain service, you'll use --destination-port. The opposite is --source-port in case you need it. So let's put this all together. This should be the command that accomplishes what we want:

iptables -A INPUT -s 200.200.200.1 -p tcp --destination-port telnet -j DROP

And there you go. If you wanted to specify a range of IPs, you could use 200.200.200.0/24. This would specify any IP that matched 200.200.200.*. Now it's time to fry some bigger fish. Let's say that, like me, you have a local area network and then you have a connection to the internet. We're going to also say that the LAN is eth0 while the internet connection is called ppp0. Now suppose we wanted to allow telnet to run as a service to computers on the LAN but not on the insecure internet. Well there is an easy way to do this. We can use -i for the input interface and -o for the output interface. You could always block it on the OUTPUT chain, but we'd rather block it on the INPUT so that the telnet daemon never even sees the request. Therefore we'll use -i. This should set up just the rule:iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --destination-port telnet -i ppp0 -j DROP

So this should close off the port to anyone on the internet yet kept it open to the LAN. Now before we go on to more intense stuff, I'd like to briefly explain other ways to manipulate rules. The -A option appends a rule to the end of the list, meaning any matching rule before it will have say before this one does. If we wanted to put a rule before the end of the chain, we use -I (capital "i") for insert. This will put the rule in a numerical location in the chain. For example, if we wanted to put it at the top of the INPUT chain, we'd use -I INPUT 1 along with the rest of the command. Just change the 1 to whatever place you want it to be in. Now let's say we wanted to replace whatever rule was already in that location. Just use -R to replace a rule. It has the same syntax as -I and works the same way except that it deletes the rule at that position rather than bumping everything down. And finally, if you just want to delete a rule, use -D. This also has a similar syntax but you can either use a number for the rule or type out all the options that you would if you created the rule. The number method is usually the optimal choice. There are two more simple options to learn though. -L lists all the rules set so far. This is obviously helpful when you forget where you're at. And -F flushes a certain chain. (It removes all of the rules on the chain.) If you don't specify a chain, it will basically flush everything.Well let's get a bit more advanced. We know that these packets use a certain protocol, and if that protocol is TCP, then it also uses a certain port. Now you might be compelled to just close all ports to incoming traffic, but remember, after your computer talks to another computer, that computer must talk back. If you close all of your incoming ports, you'll essentially render your connection useless. And for most non-service programs, you can't predict which port they're going to be communicating on. But there's still a way. Whenever two computers are talking over a TCP connection, that connection must first be initialized. This is the job of a SYN packet. A SYN packet simply tells the other computer that it's ready to talk. Now only the computer requesting the service sends a SYN packet. So if you only block incoming SYN packets, it stops other computers from opening services on your computer but doesn't stop you from communicating with them. It roughly makes your computer ignore anything that it didn't speak to first. It's mean but it gets the job done. Well the option for this is --syn after you've specified the TCP protocol. So to make a rule that would block all incoming connections on only the internet:

iptables -A INPUT -i ppp0 -p tcp --syn -j DROP

That's a likely rule that you'll be using unless you have a web service running. If you want to leave one port open, for example 80 (HTTP), there's a simple way to do this too. As with many programming languages, an exclamation mark means not. For instance, if you wanted to block all SYN packets on all ports except 80, I believe it would look something like this:

iptables -A INPUT -i ppp0 -p tcp --syn --destination-port ! 80 -j DROP

It's somewhat complicated but it's not so hard to comprehend. There's one last thing I'd like to cover and that's changing the policy for a chain. The chains INPUT and OUTPUT are usually set to ACCEPT by default and FORWARD is set to DENY. Well if you want to use this computer as a router, you would probably want to set the FORWARD policy to ACCEPT. How do we do this you ask? Well it's really very simple. All you have to do is use the -P option. Just follow it by the chain name and the new policy and you have it made. To change the FORWARD chain to an ACCEPT policy, we'd do this:iptables -P FORWARD ACCEPT

Nothing to it, huh? This is really just the basics of iptables. It should help you set up a limited firewall but there's still a lot more that I couldn't talk about. You can look at the man page man iptables to learn more of the options (or refresh your memory when you forget). You can find more advanced documents if you want to learn some of the more advanced features of iptables. At the time of this writing, iptables documents are somewhat rare because the technology is new but they should be springing up soon. Good luck.